The maxim “The worse things get, the better!” resonates most strongly with radical activists, revolutionaries, and strategic opportunists who view escalating crises not as disasters, but as accelerants for profound change. It’s a mindset that embraces short-term suffering as the price for long-term transformation, often rooted in the belief that complacency only entrenches the status quo. Below, I’ll outline key groups or figures who might adopt it, drawing on historical, political, and contemporary examples—then tie it directly to the Scottish independence scenario.

Core Adopters of the Maxim

These are archetypes who see deterioration as a feature, not a bug:

- Revolutionary Marxists and Leninists: Drawing from Vladimir Lenin’s tactic of “sharpening the contradictions,” they argue that worsening exploitation under capitalism exposes its flaws, radicalizing the masses toward uprising. The phrase captures this: economic pain (e.g., recessions or inequality spikes) isn’t to be mitigated—it’s to be amplified to hasten collapse and rebirth. Modern echoes appear in Trotskyist groups or far-left parties like certain factions within France’s La France Insoumise, who might cheer fiscal austerity as a spark for anti-EU revolt.

- Anarchists and Insurrectionary Movements: Thinkers like Mikhail Bakunin or contemporary autonomists (e.g., in Italy’s Tute Bianche or Greece’s anti-austerity networks) often frame chaos as a liberatory force. The worse governance fails, the quicker people reject authority altogether. This shows up in environmental radicals too—deep green anarchists who might say climate disasters “the better” because they force societal breakdown and localized, sustainable alternatives.

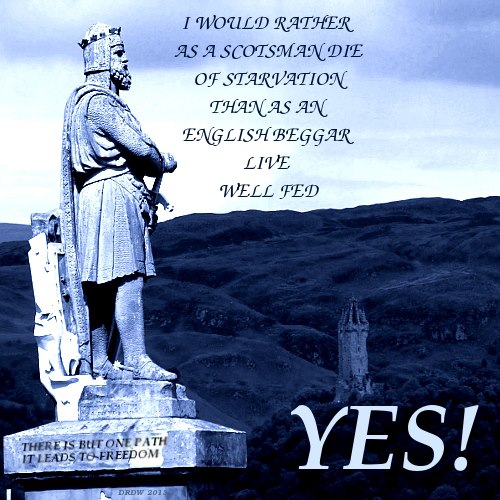

- Nationalist Separatists in Stagnant Campaigns: In independence movements facing entrenched opposition, hardliners adopt this to justify enduring hardship. It’s a siege mentality: if polite persuasion fails, let the union’s flaws (economic woes, cultural erosion) do the convincing. Your example fits perfectly here—more on that below.

- Doomsday Preppers and Accelerationist Subcultures: Online fringes, including some alt-right or effective accelerationism (e/acc) communities, pervert it into nihilism: sabotage systems to speed up the “inevitable” reset. But on the left, it’s more constructive, like in degrowth advocates who welcome recessions as a curb on overconsumption.

- Contrarian Investors and Opportunists: Less ideological, but figures like hedge fund managers (e.g., those betting against markets in 2008) or crypto anarchists embody it practically: crashes create bargains, so “let it burn” to buy low.

Application to Scottish Independence

The independence movement post-Alex Salmond illustrates the maxim in action. Since Salmond’s 2014 departure from the SNP (and his later founding of the Alba Party), polls show Indy support hovering around 45-48%—stagnant, despite tactical shifts like Sturgeon’s gender reforms, Haroon’s culture crashes or Swinney’s leadership wobbles. Unionist “loyalty” (bolstered by Better Together’s emotional appeals and Westminster’s fiscal carrots) has proven Teflon-coated against data on oil revenues, NHS divergences, or Brexit fallout.

Enter the accelerationist wing of the Indy side: Wings Over Scotland bloggers, Alba diehards, or even some SNP backbenchers who whisper that more “pain” could tip the scales. Examples include:

- Economic Squeeze as Catalyst: With UK-wide issues like energy bills, Truss/Kwarteng-era chaos, or post-Brexit trade friction hitting Scotland hard (e.g., fishing quotas or EU border snags), the argument goes: Let Westminster’s mismanagement fester. If rUK inflation or austerity bites deeper, enough No-voters—perhaps 5-7% in key demographics like middle-class suburbanites in the Central Belt—might cross over, blaming the Union. It’s “the worse (for the UK), the better (for Indy).”

- Cultural/Policy Grievances: SNP missteps (e.g., the Alex Salmond trial fallout or stalled IndyRef2) have alienated some, but hardliners say amplify the divide—push deposit return schemes or hate crime laws that clash with rUK norms, forcing Scots to confront “two-tier” citizenship.

- Real-World Echoes: In recent discourse, pro-Indy voices on platforms like X have floated this explicitly. For instance, amid 2025’s hypothetical UK fiscal woes (assuming ongoing stagnation), one commentator noted: “The worse things get, the more they shout, Indy!”—framing SNP woes as ironic fuel. Similarly, in parallel separatist chats (e.g., Alberta’s oil disputes), it’s “Good. The worse things get, the stronger the push for independence.”

Critics call this cynical gambler’s logic—risking real suffering for a coin flip. But for the maxim’s adherents, it’s pragmatic realism: reasoned arguments built the 2014 surge to 45%, but emotion (and pain) wins referendums. If UK-Scotland tensions escalate (say, over North Sea resources or net-zero mandates), watch for this mindset to gain traction in Indy circles.

Successful Examples of the “Worse Things Get, the Better” Strategy in Recent Politics

The strategy called accelerationism or “worsening to catalyse change”—involves allowing or leveraging deteriorating conditions (economic hardship, corruption, inequality, or governance failures) to erode support for the status quo and build momentum for radical shifts, such as regime change, independence, or populist takeovers. While it’s risky and can backfire (e.g., leading to prolonged chaos without resolution), there are notable cases post-2000 where escalating crises did precipitate successful political transformations. “Success” here means the strategy achieved its proponents’ goals, like ousting incumbents, policy reversals, or structural reforms, even if long-term stability varied.

I’ll focus on recent examples (roughly 2000–2025) drawn from global politics, including revolutions, uprisings, and independence movements. These aren’t always explicitly “accelerationist” in ideology but align with the maxim by turning worsening conditions into leverage for change. I’ve prioritized cases with clear outcomes, using a table for comparison where it clarifies patterns.

Key Examples

- Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution (2010–2011): Amid soaring unemployment, food price spikes, and corruption under President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s 23-year rule, self-immolation protests sparked nationwide unrest. The “worse is better” dynamic played out as economic despair radicalized the middle class and youth, eroding loyalty to the regime. Ben Ali fled in January 2011, leading to democratic elections, a new constitution in 2014, and initial reforms (e.g., freer press and elections). Though backsliding occurred under President Kais Saied by 2021 (e.g., power consolidation), the uprising achieved a transition from autocracy to flawed democracy, with GDP growth rebounding post-2011. This is often cited as the Arab Spring’s lone “success,” where crisis accelerated demands for accountability.

- Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya Uprising (2022): A severe economic collapse—fueled by debt, COVID-19 fallout, and government mismanagement—led to shortages of fuel, food, and power, with inflation hitting 70%. Protesters, embracing a “let it burn” mindset to expose elite corruption, occupied key sites and forced President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation in July 2022. The new government under Ranil Wickremesinghe (and later Anura Kumara Dissanayake after 2024 elections) implemented reforms, including anti-corruption drives and IMF-backed stabilization, restoring some growth by 2025. Citizens credit the crisis for breaking decades of dynastic rule, proving worsening can force systemic resets in corrupt systems. Parallels to your Scottish Indy example: Stagnant unionist loyalty gave way under shared pain.

- Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution (2013–2014): President Viktor Yanukovych’s pivot away from EU integration amid economic stagnation and Russian influence sparked protests in Kyiv. As police crackdowns worsened (killing over 100), it galvanized broad support, including from former loyalists, leading to Yanukovych’s ouster in February 2014. This shifted Ukraine toward Western alignment, with EU association agreements and NATO aspirations. Despite ongoing war post-2014 annexation of Crimea, the revolution succeeded in reorienting national identity and politics away from Moscow’s orbit. Here, escalation unified disparate groups, much like how Indy hardliners hope UK-wide woes could sway unionists.

- Bangladesh’s Student-Led Uprising (2024): Quota system favoritism, coupled with economic slowdown (post-COVID joblessness, inflation), boiled over into protests against Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s authoritarian rule. As repression intensified (hundreds killed), it broadened into a mass movement, forcing Hasina’s resignation in August 2024. An interim government under Muhammad Yunus pledged reforms, with early signs of freer elections and anti-corruption measures by 2025. This rapid success shows how youth-driven crises can topple entrenched leaders in developing economies.

- Nepal’s People’s Movement II (2006): Decades of monarchy-corrupted governance worsened by civil war and economic isolation led to a 19-day nationwide strike and protests. King Gyanendra’s power grab backfired, accelerating demands for democracy. The uprising ended the monarchy, establishing a republic in 2008 with a new constitution in 2015. Despite ethnic tensions, it achieved federalism and inclusion, transforming Nepal from absolute monarchy to multiparty democracy.